2.4 Program Verification

In this section, we will learn how to use Cyclone to verify some simple programs. In program verification, a computer program can be formally proved using some abstract mathematical models and formalisms. These models or formalisms could be state-based structures or algebra-based formalisms. For example, one can use Hoare logic to verify the correctness of an algorithm. Similarly, a cyclone specification captures a graph-based structure. Hence, we can model a program by using cyclone provided state-based/graph structures.

2.4.1 Sequential Code

For example, we can use Cyclone to verify the following piece of code:

[x = c/2;]

t = x;

x = x - y;

y = t + y;

[c = x + y;]

where x,y,c and t are integers. Our precondition here is: x=c/2; Now, we would like to check after running this piece of code whether the postcondition x+y==c holds.

One of the many ways of using Cyclone to check this condition is to write each line of the code inside a state and asks Cyclone to find a sequential "execution" order such that the condition is true. Thus, we can turn this piece of code into the following Cyclone spec:

graph Verification {

int c;

int x = c/2; //precondition

int y;

int t;

start normal state S0 { t = x; }

normal state S1 { x = x - y; }

normal state S2 { y = t + y; }

trans { S0 -> * }

trans { S1 -> * }

trans { S2 -> * }

goal {

assert ( x+y == c ); //postcondition

check for 2 reach (S1,S2)

}

}

Here, we used anonymous edges to model all possible "execution" sequences. We then use an assert statement to ask Cyclone to find an "execution" sequence (with 3 instructions) that can make the postcondition true based on our precondition. After checking all possible "execution" sequence with a length of 2, Cyclone successfully returns the sequence: S0->S1->S2. Indeed, this is the same sequence as our code block. In fact, this is the only sequence (if we use enumerate) that can make our postcondition become true. Thus, this proves the correctness of this piece of code. That is: given the precondition we should be able to derive our postcondition.

2.4.2 If-else

Obviously, one can write a piece of code using if-else structures. An if-else structure typically deals with a guard. A guard is a boolean expression that must evaluate to true in order to execute code section defined in an if branch otherwise else branch is executed.

In this case, one can use a conditional transition to model a guard. For example, if we have the following piece of code

[true]

a = x + 1;

if ( a-1 == 0)

y = 1;

else

y = a;

[y = x+1;]

the precondition here is true and we would like to prove our postcondition: y==x+1

We use the same idea as previous section. We model each instruction as a state but establish one conditional transition for the guard. Thus, we have the following Cyclone spec:

graph Verification {

int a;

int x;

int y;

start normal state B0 { a = x + 1; }

normal state B1 { y = 1; }

normal state B2 { y = a; }

trans t1 { B0 -> B1 where (a - 1 == 0);}//conditional transition

trans t2 { B0 -> B2 }

goal {

assert !(y == initial(x) + 1); //postcondition

check for 1 reach (B1,B2)

}

}

xxxxxxxxxx3 1goal { 2 check for 2,3,4,5 reach (Fall,Bounce)3}cyclone

Note that in the goal section, we ask Cyclone to find a counter-example (sequence) that can break our postcondition. The keyword initial refers to a state of a variable before entering a start state. In this example, Cyclone is not able to find a counter-example. This is because no matter which branch we choose Cyclone always proves our postcondition is true. Thus, we prove this code by finding no counter-examples.

2.4.3 Loops

Simiarly, we can also use Cyclone to verify a program that uses a loop structure. For example, we have the following piece of code:

[true]

i = 0;

z = 0;

while ( i != y ){

i = i + 1;

z = z + x;

}

[z=x*y;]

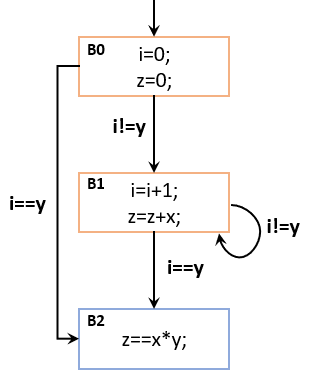

The precondition here is true and postcondition here is z==x*y. Clearly, we can model the above code into the following control flow diagram.

The orange boxes represent our source code and blue box indicates our postcondition. Each guard is marked as a label over a transition. To prove a loop, we need to explicitly specify a loop invariant in Cyclone. In this example, it is quite obvious that z==x*i is our loop invariant. Recall that a loop invariant must hold before, during and after the loop. We now can specify our loop invariant by using an invariant statement. Thus, our complete cyclone specification is shown below:

graph Verification {

int i where i >= 0; //counter i is always positive

int z;

int x;

int y;

start normal state B0 {

i = 0;

z = 0;

}

normal state B1 {

i = i + 1;

z = z + x;

}

normal state B2 {

z = x * y;

}

trans t1 { B0 -> B1 where ( i != y );}//loop guard

trans t2 { B1 -> B1 where ( i != y );}//loop guard

trans t3 { B0 -> B2 }

trans t4 { B1 -> B2 }

invariant loop_inv { z == x*i; }//loop invariant

goal {

check each 1,2 condition (B1^{0:1}) reach (B2)

}

}

From Section 2.2, we know that an invariant statement in Cyclone indicates that the invariant must hold in every state. In this example, this means that our loop invariant (z==x*i;) must stay true in states: B0, B1 and B2. In fact, these states model code blocks before (B0), during (B1) and after the loop (B2).

In our goal section, we ask Cyclone to discover a counter-example (execution sequence) that goes through our loop (code block B1) zero or at least once and can break our invariant. However, Cyclone cannot discover such an example for this code block. Hence, we formally prove (partial) correctness of this program.

Practice: Can you use Cyclone to prove total correctness of the above program ?

Execution Result

Press 'run' to execute the code and see checking results.

Execution server didn't supply any information

URL: /server